The Mourners, Dallas Museum of Art, through January 2, 2011

As a closet medievalist, I was ecstatic to hear that The Mourners was coming to the Dallas Museum of Art. This never happens. Dallas is just not a hub for medieval studies. And that it is such a significant exhibition is icing on the cake.

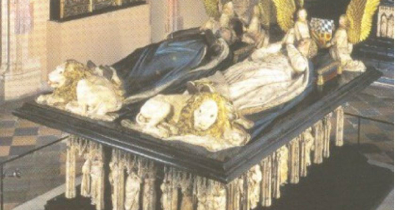

At their home in Dijon, these Mourners, or pleurants, meander through an architectural setting holding up the tomb of John the Fearless, the second Duke of Burgundy (see above). His father, Philip the Bold, was the first to have this unique artistic convention as part of his tomb. In Philip’s case, in many ways echoed his real passing from this world to the next.

As the 4th son of John the Good, King of France, Philip was granted Burgundy as an apanage, a territory that technically belonged to the French crown but was otherwise his to watch over as long as he produced a male heir. Through his own successful marriage to Margaret of Mâle and those of his children, he parlayed this parcel of land into an empire unto itself that ultimately included most of modern day Belgium and Holland. Though his official residence was in Dijon, in present day France, he spent a good deal of time in Paris and throughout his realm. And as any proper noble of the time, he commissioned the best artists to work for him. Philip and his brothers, among them Jean, Duc de Berry, showed a preference for the kind of realism that was being produced in his northern territories of Flanders and Holland.

One of the artists working for him in Dijon, Claus Sluter, created elegant figures swathed majestically in voluminous textiles, the very material that helped make the Low Countries an economic powerhouse of the 14th & 15th centuries. While Sluter is best known for the Well of Moses commissioned by the Duke for the Chartreuse de Champmol, it was the tomb that he created for Philip for the same monastery that made a mark on funerary sculpture for the next century.

Philip died at Hal, near Brussels. While his viscera remained in the church at Hal and his heart was sent to the royal burial church of St. Denis in Paris, the rest of him went via long cortège back to Dijon. It is precisely this procession that Sluter captured in the tomb figures that surround the base of Philip’s tomb. Meandering through an architectural framework, the figures reflect sorrow, contemplation and reverence for the duke. Sluter himself died in 1404, before the tomb was finished. His nephew, Claus de Wevre, took over his workshop, completing the work in 1414.

Philip’s son, John the Fearless (Jean sans Peur) was an equally able ruler and further expanded the Burgundian Empire. He not only shared the family’s aesthetic sensibilities but he also wanted to follow the traditions set forth by his father, thus shaping a dynastic style. And while he wanted “a sepulcher similar to the one of my late father”, it wasn’t until long after John’s murder in 1419 that the commission was finalized by Philip the Good, the third Duke of Burgundy.

Ultimately, it took until 1443 for Philip the Good to finalize a contract with Jean de la Huerta for the making of the tomb. We know that De la Huerta left Dijon in 1456, with the tomb near its completion. While he executed many of the mourners seen in this exhibition, another sculptor, Antoine le Moiturier, had the task to “finish, polish and complete the mourners”. The completed tomb was finally installed in 1470, over a half century after John’s passing.

It is impossible to discern the hand of De la Huerta from that of Le Moiturier, especially since a few of the mourners are direct copies of the ones executed by Sluter for Philip the Bold’s tomb. Given their parameters, these two talented sculptors did not have the opportunity to unleash their creativity. The irony is that while one commission was so innovative and original, the next, was, by design, planned to be conservative.

Having said that, however, there is nothing boring about this exhibition. Each mourner is unique. Some wear purses and belts over their sumptuous alabaster cloaks while others wear only their grief. Some carry gilt edged books, others walk solemnly through the centuries. It is a magnificent exhibition.

I saw the exhibition in New York this past spring, when it was at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. There, the mourners walked double file along a single plinth, in the middle of the cavernous main medieval gallery. This area is also on the path from the Museum’s main entrance to the cafeteria so I am sure far more people saw it than had planned to. People did stop to look carefully at each figure. However, it was hard to achieve a feeling of solemnity in such a bustling space.

The DMA’s installation is far more successful. In its own gallery, there is a greater air of sanctity for these figures. While there is still a plinth with several figures on it, it lacks the same monolithic feeling of the New York installation. Here, other figures are clustered three or four on pedestals throughout the gallery, interacting with each other and the viewer. The gallery is in low light except for the spotlights on the figures. Truly breathtaking.

Dallas is also fortunate to have this exhibition during the fall, when life goes from chaotic to hyper-chaotic through the holidays. Let this exhibition give you a respite from busy schedules, deadlines, and e-mails. Contemplate, enjoy and come away from it feeling serene.